Origins of Fontburn

To those of us who spent our childhood at Fontburn, or to someone like myself who travelled to school in Morpeth daily by train for five years, returning home meant just that – the view from the viaduct, the filter beds laid out neatly, the cottages, a welcoming sight. Home.

How different and perhaps daunting it must have seemed to those families in 1901 travelling in for the first time, to join their menfolk already at work on the dam. They would have looked down from the vantage of the viaduct and seen the raw workings of the new Waterworks enterprise laid out below, a sea of mud, tramways, machinery, navvies and craftsmen hard at work, serviced by a ‘shanty town’, a hutted village, that was to be their new temporary home. Perhaps they looked and wondered at the bleakness of the place, in contrast to the familiar teeming streets of Tyneside. Civilisation may have seemed far away in this windswept muddy spot miles from the nearest village let alone the nearest town.

The railway line was here long before the Waterworks – 30 years before, in fact, built by private landowners as a commercial venture to establish a link with Scotland. The intention was to build a cross-country line north from Morpeth which would link up with other branch lines east and west such as the north Tyne at Redesmouth. Built in two phases, the Morpeth – Scots Gap section was completed in 1862, and the second, Scots Gap - Rothbury, in 1870. During these years ownership changed as the venture ran into financial difficulties, and eventually came under the control of the North British Railway Company. It remained a single track line with crossing loops at Rothbury and Scots Gap and a refuge siding at Ewesley. The initial dream of providing an alternative cross-Border route was left unfulfilled. Instead it terminated at Rothbury, and became an essential means of travel for people of the villages and hamlets it passed by, as well as servicing several colliery, mine, quarry and lime workings on the way. To the folks of Fontburn Waterworks it was their lifeline.

Daisy Cottages were built to serve the railway long before Fontburn came into being. The grass track is where the rail lines used to run. The picture was taken by Jack Hepburn in the 1970's, looking south towards the site of the former station.

Click on picture for larger view

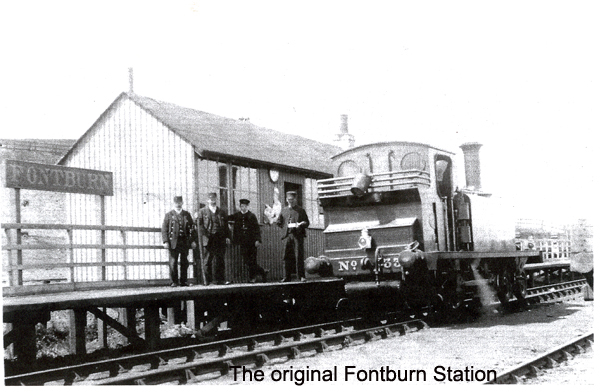

The existence of the line would have been an important factor in the Tynemouth Water Company’s considerations, when looking for an appropriate site to dam the Font. It provided a ready-made means of transport into an otherwise inaccessible and inhospitable area, with an impressive viaduct already in place. The building of the viaduct had not been without its difficulties. With its twelve 30ft spans and a maximum height of 60ft, it was flanked by lofty embankments that had been problematic when under construction in the 1860s. In addition, it was close to the established Whitehouse Limeworks, said to have been used during the building of the viaduct, and had sidings, a nearby kiln, and a tramway linking Fontburn station to quarries further east, at Whitehouse, and later Ewesley. These quarries would provide essential building materials. These factors may well have swayed the decision to build the Fontburn Dam and Waterworks. Thus a site and its new name were chosen.

The search for a reliable water supply was a feature of nineteenth century living. Towns were becoming unhealthy places, poisoning themselves with their own human and industrial waste. This waste turned rivers into open sewers, massively impacting on public health. As populations exploded in the industrialised areas, such as Tyneside, so the epidemics of killer diseases such as typhoid and cholera became commonplace. Seeping cesspits fouled water supplies, and no-one was immune – not even the Royal Family, when Prince Albert succumbed, probably to typhoid, in 1861. Life expectancy, if a child survived infancy, fell as low as twenty six years in some city areas.

Massive investment in public health was needed, but was slow in coming in a Victorian society that lacked the political structure to carry this out. Following the ‘Great Reform Acts’ that widened the vote, so began programmes of social improvement. Local Government Boards responsible for the health of an area led the way. These eventually became local government bodies with wide-ranging powers. To replace groundwater supplies, surface reservoirs had to be built. All over the country plans became reality, of drawing water from lakes and of damming valleys to construct reservoirs that would supply clean water to a growing population. This went hand in hand with improved sewerage systems, as understanding grew of the causes of diseases such as typhoid and cholera. The turn of a tap revolutionised domestic life, as did the advent of the water closet. The demand for water rocketed.

Tyneside was not immune, with the Newcastle and Gateshead Water Company leading the way. Permission by Act of Parliament enabled newly formed corporations to look for water outside urban limits and so on 2 August 1898 was passed ‘An act to empower the Corporation of Tynemouth to obtain water from the River Font in the county of Northumberland for the supply of the borough of Tynemouth and adjacent places for other purposes’. There had been a previous Act authorising the Tynemouth borough, to include Whitley Bay and Monkseaton, to purchase water from the North Shields Waterworks, but this had proved inadequate, as had the attempt to purchase from Newcastle and Gateshead Water Co. Tynemouth was to have their very own reservoir, built high up the Font, around Hollinghill, Green Leighton and Ritton White House.

The land involved belonged to three estates: to the north, the Duke of Northumberland; to the east, the Ordes of Nunnykirk; and to the south, the Trevelyans of Wallington. A limit of £430,000 was laid down for the ‘purchase of land and the construction of new works’ and the pipe line down to the coast, with guidance on how this money was to be raised and how to be repaid. A further limit of sixty years was placed for repayment of any loan. The work had to be completed within ten years and there were other stipulations relating to the building of the embankment, outlet tunnel and floodwater channel. Negotiations had to include the North Eastern Railway Company, as the pipe line needed to pass below the viaduct. The flooded valley above the dam would drown out a road that ran between Greenleighton and Newbiggin farm. That road had eventually linked with the main Rothbury road. A new road had to be built, the one we know today that comes in past Roughlees into Fontburn and onward to Newbiggin.

Thus the stage was set for work to begin. As the nation emerged from the Boer War, and Victorian times gave way to Edwardian, so the settlement at a new place to be known as ‘Fontburn’ began. The first sod was cut in October 1901.

The Proudlocks of Daisy Cottages in 1896.

(Picture probably taken by an itinerant photographer)

Click on picture for larger view

We are fortunate to have many archive pictures that show the building of the dam and works, though we have little or nothing by way of other documentary evidence. Bowtell in his book ‘Dam Builders Railways from Durham’s Dales to the Borders’ details the teething problems in getting the work underway. Sadly those who worked so hard during the years 1901 – 1908 are no longer here to tell their own story, but their images live on in the photographs. A hutted village, the very first community, grew into being enabling wives and children to join their men folk.

In other parts of Northumberland, such as at Catcleugh, hutted villages already existed, looking very similar to Fontburn from photographic evidence. Fontburn Waterworks or, rather, the Fontburn community of families that came to live and work there after completion in 1908, would become a focal point for the neighbourhood, not least because families meant children, and children, from 1902, meant compulsory and free education. Fontburn School would play a vital role in community life as the new Fontburn community established itself.

Further Reading:

1. Bowtell, H D, (1994) Dam Builders’ Railways from Durham’s Dales to the Border, pub Plateway Press

2. Jenkins SC (1991) The Rothbury Branch , pub Oakwood Press

Website created by WarrenAssociates 2007

Website hosted by Vidahost

Copyright © Maud Isabel Warren 2008

www.Fontburnremembered.co.uk